Preserve the Jacob Fontaine Gold Dollar Building

As the last remaining structure of Wheatville, a mostly forgotten community of persons who were formerly enslaved in Texas and across the US, the Jacob Fontaine Gold Dollar Building at 2402 San Gabriel Street is an important physical foundation for Black social memory in Austin. While it is a City of Austin Landmark, the structure has endured significant physical changes over the years—alterations that are nevertheless of historic age, part of the building’s historic significance. This statement reanimates and substantiates the history of the structure and the freed-person community originally surrounding it, establishing the Gold Dollar Building as a valuable site for the city’s Black heritage and collective historical memory. In doing so, it makes the case for its treatment as a commemorative space and calls into question allowing further physical modifications to the structure.

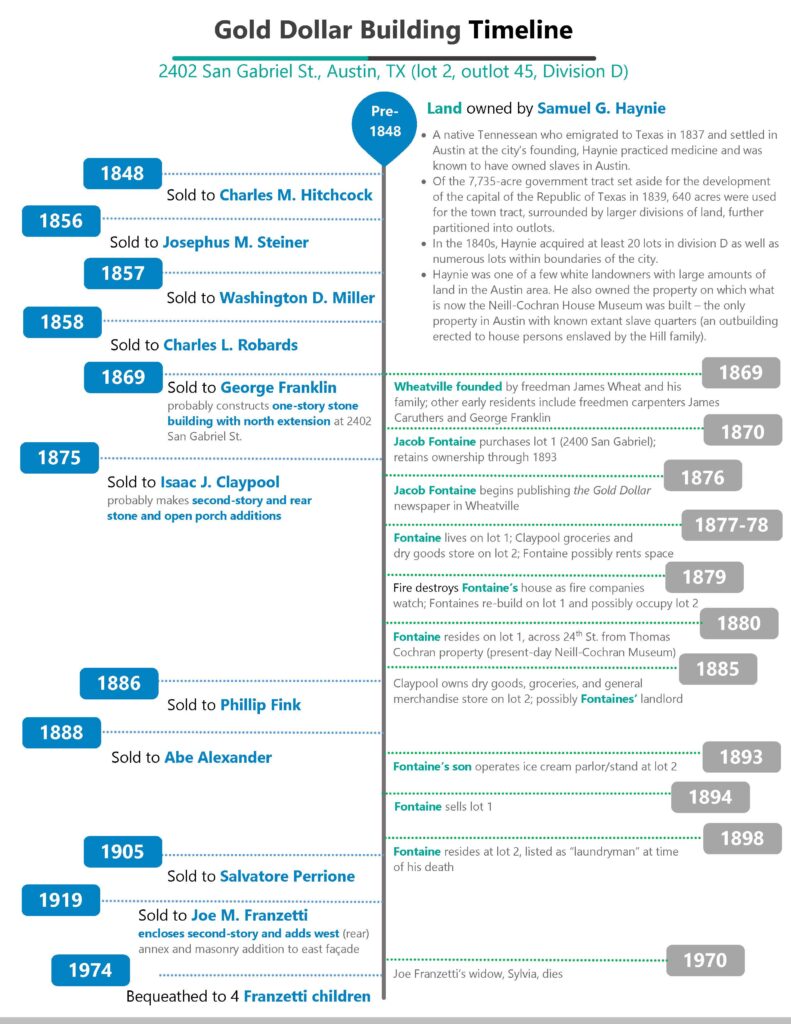

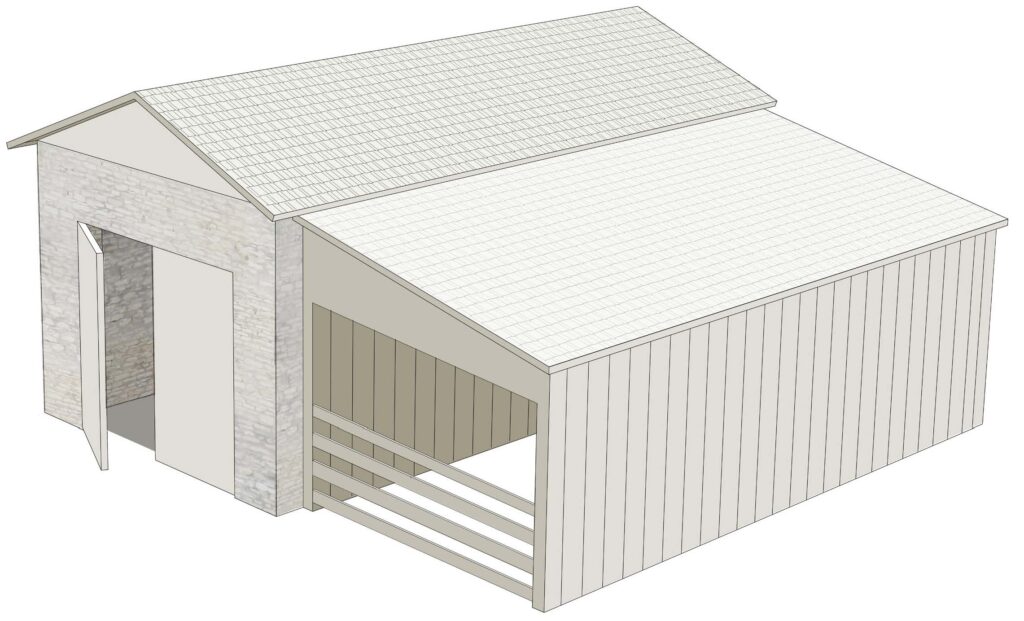

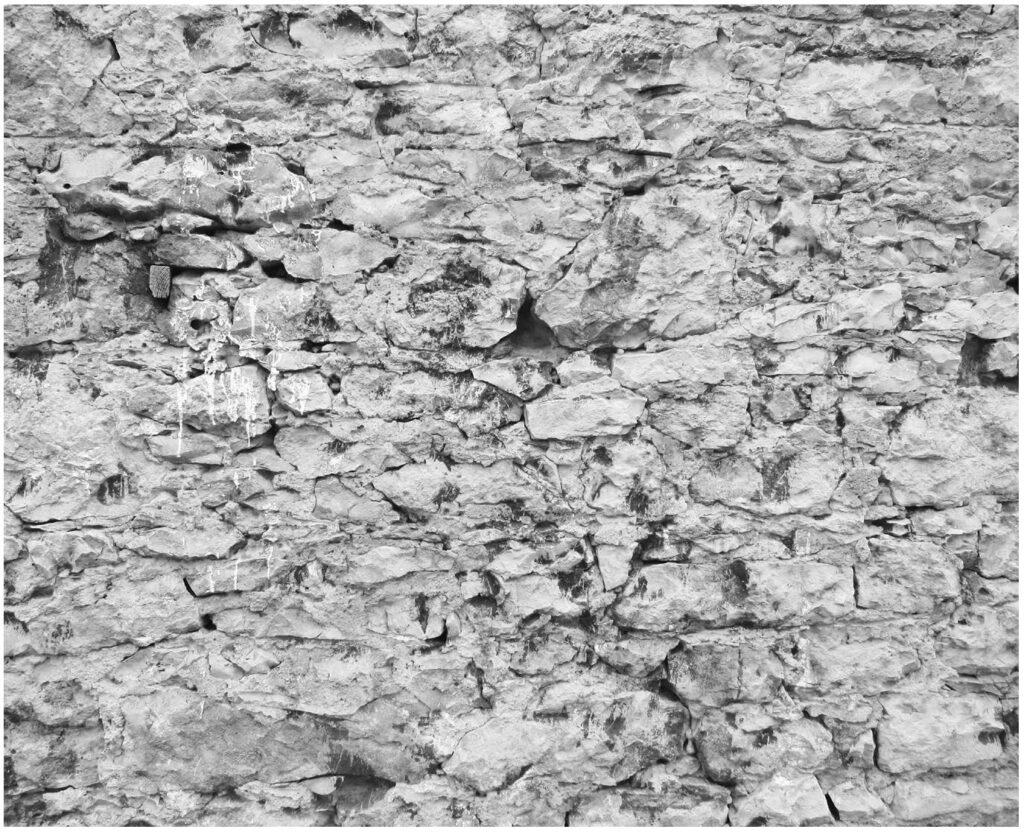

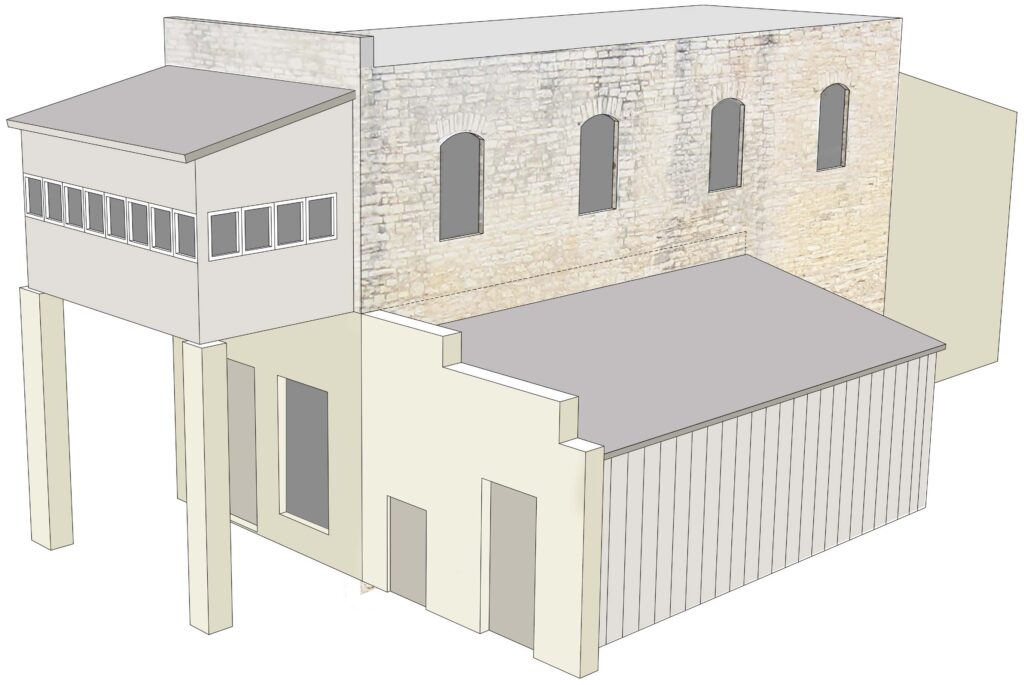

During a time when Austin’s Black population was at about 36%, several white men who owned property in Division D began to sell lots to freedmen. Joseph Caruthers, a freedman from North or South Carolina, acquired property in outlot 46, including the site of present-day 900 West 24th Street, from Colonel John M. Thomas in December 1868. Shortly after, in the spring and summer of 1869, a freedman from Arkansas, James Wheat, acquired three parcels from Thomas, also in outlot 46 and including present-day 2409 San Gabriel. The Wheat family became the namesake, if not the founders, of a freedom colony or freedmen’s community called Wheatville. Other Black folks soon also bought small lots in the area—including George Franklin, who bought property at present-day 2402 San Gabriel St. that same year and set up a wagon park on it—and the self-directed community began to grow. The increase in that property’s value indicates that Franklin developed it in some way, possibly with a one-story, stone building with a lean-to (FIG 1).

On March 22, 1870, Black visionary leader Jacob Fontaine acquired the adjacent lot (lot 1, 2400 San Gabriel St.), where he began living with his extended family. Fontaine was a prominent Baptist minister who had been previously enslaved by Edward Fontaine, the personal secretary of Texas President Mirabeau B. Lamar.

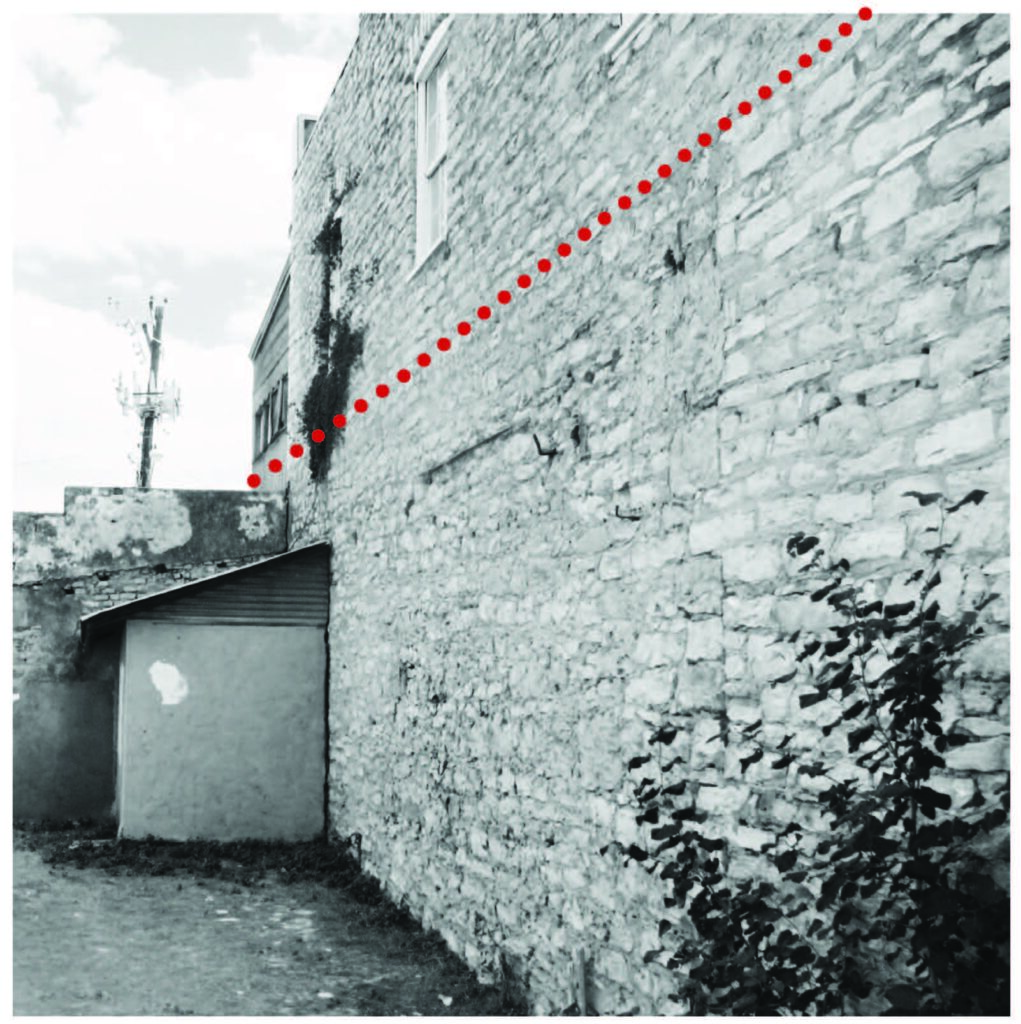

Franklin sold lot 2 and any improvements to Isaac Claypool in 1875. The now-iconic, two-story stone building was realized soon after, likely expanding Franklin’s original building and probably constructed using Black labor from the surrounding community (FIG 2 & 3).

At the 1875 Austin city census, Claypool and Fontaine were neighbors. Claypool lived as a bachelor with an extended family of freedmen—the Johnsons and Paynes—the male members of which were probably involved with the construction projects on the property. The building at no. 2402 that they expanded has stood at this location on San Gabriel St., previously Wheatville’s main thoroughfare, for almost 150 years.

Reverend Fontaine began publishing the Gold Dollar, an early Black newspaper in the south and one of the first Black newspapers west of the Mississippi, from his home at 2400 San Gabriel. In addition to his work as a preacher, teacher, and newspaper publisher, Fontaine was a prominent Black Republican, one of the first Black people to vote in Travis County, and an active participant in the Black politics of Texas. As a renowned member of the Black community whose political activity was as conspicuous as it was acclaimed, Fontaine also became a target of racial violence. In 1879, persons unknown set on fire and burned to the ground his home and newspaper’s headquarters at no. 2400 as fire companies watched. This act of violence did not hinder Fontaine’s activism; he was a delegate to the 1880 Greenback Party National Convention in Chicago and instrumental in securing the vote of Black Texans for the establishment of The University of Texas in Austin (UT) in 1883. Although the Fontaine home at no. 2400 appears to have been rebuilt (Austin city directories give 2400 San Gabriel as Fontaine’s address throughout the 1880s), the arson may have prompted the family’s rental of the Claypool building at no. 2402 as a residence and business at various intervals. Subsequent owners of 2402 San Gabriel were primarily absentee landlords from whom the Fontaines probably rented.

According to Fontaine family oral history, the two-story stone building at 2402 San Gabriel was the location of the Gold Dollar newspaper and original home for New Hope Baptist Church, founded by Fontaine in 1887. The Fontaines’ eldest son, George, was listed as operating an ice cream stand at the stone building in the 1893-1894 city directory. By 1894, any connection that the Fontaines retained to no. 2400 ceased when Reverend Fontaine sold lot 1 that year. The 1895-1896 city directory indicated that Reverend Fontaine resided a block away, on West 24th St., with his daughter, Melissa Gordon, and son-in-law. However, George Fontaine, then listed as a painter, appears to have continued to occupy no. 2402. Jacob Fontaine was again listed as residing there in the 1897-1898 city directory, where his occupation was described as laundryman, while Italian grocer Simon Chiaperro occupied the former Fontaine property at no. 2400.

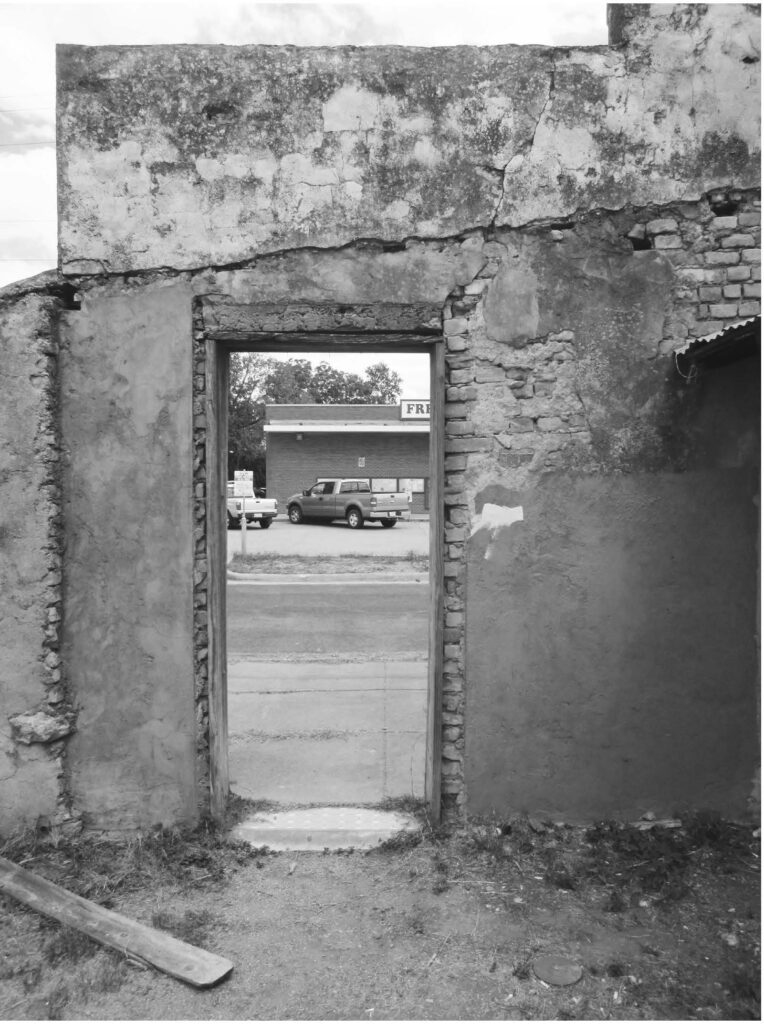

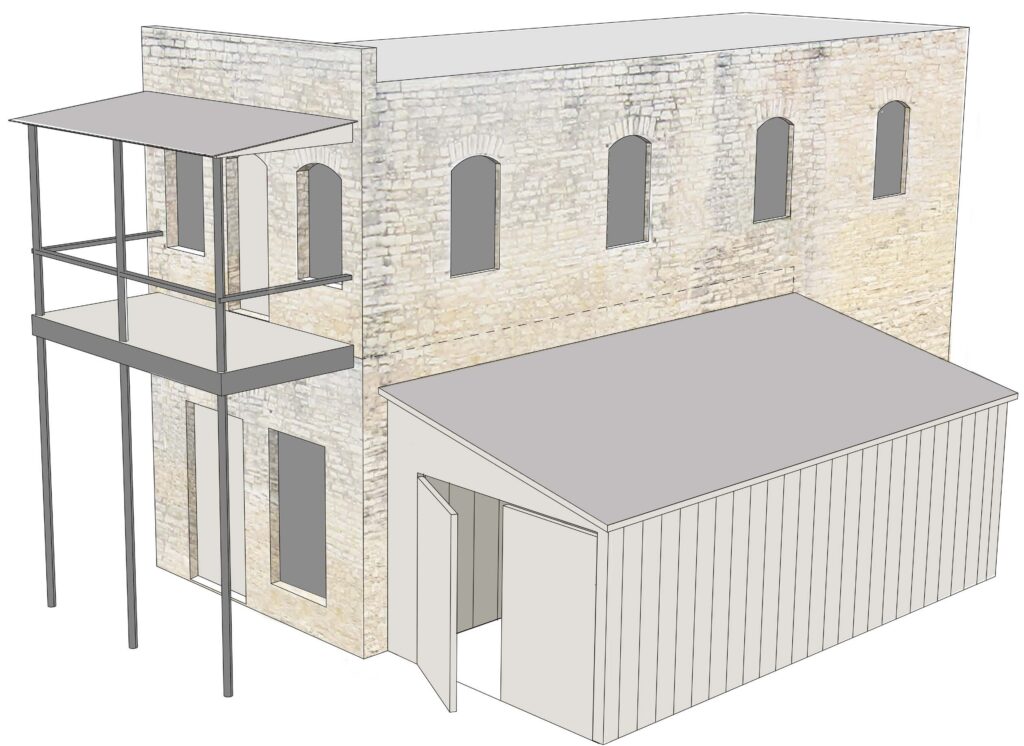

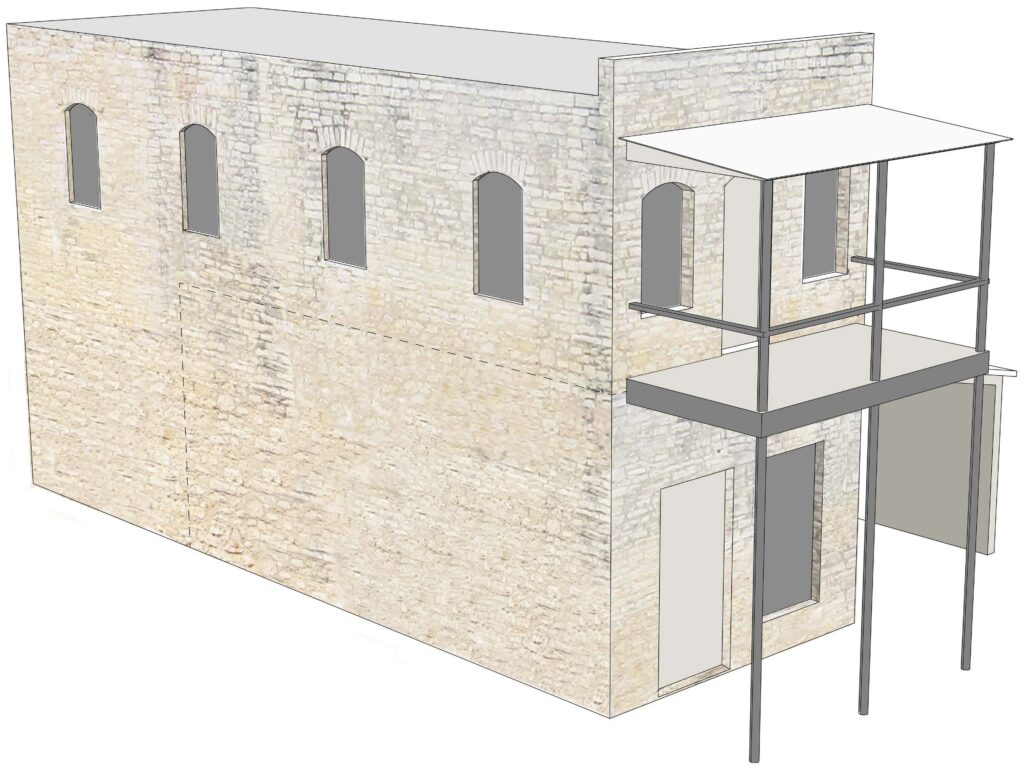

Jacob Fontaine died in 1898 and was interred in the Colored Grounds at Austin’s Oakwood Cemetery. The exact location of his tombstone is unknown, but a historic marker in the cemetery—though, interestingly, not one in Wheatville—is the only such public recognition of his contributions to Austin and the State of Texas. Although no longer formally occupied by Black residents with the arrival of Italian immigrants and other white Austinites to Wheatville in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the building at 2402 San Gabriel remained integral to Wheatville’s Black community through its use as a grocery and dry goods store, then run by the Franzetti family, who altered the building to its current appearance (FIG 4). In 1977, while still owned by members of the Franzetti family, 2402 San Gabriel was designated as a City of Austin Historic Landmark, named the “Franzetti Building.”

Similar to other freed-person communities established at the time, previously enslaved people created Wheatville as a collective refuge during Reconstruction, allowing newly-freed Black people to escape the near-slavery of debt indenture on rural plantations and farms. Black people from more than a dozen different US states were able to unite their families, take control of their family relations, and build institutions like churches and schools on Wheatville land. They exhibited a Black collective agency not possible in other areas, creating a self-directed community in direct opposition to those in Texas and the rest of the country who actively attempted to maintain a white supremacist social order. As happened in Fontaine’s case, some whites in nearby Austin acted violently to limit such demonstrations of Black agency.

In 1880, the Wheatville freedom community contained 26 households and 125 persons. As Austin expanded, and especially after UT opened in 1883, Wheatville remained a partial refuge from Austin’s increasingly virulent anti-Blackness and the area near West 24th and Rio Grande Streets became a color line separating the Black enclave from the white city. Following the trend of Jim Crow nationwide, the city of Austin codified racist development in its City Plan for Austin (1928), moving to establish a “negro district” east of East Avenue and implementing strategies and policies that denied city-provided amenities—such as sewage lines, schools, and recreational facilities—to Black communities and neighborhoods outside of the “district.” In enforcing this infamous plan, the city deprived the Wheatville area of garbage collection and other essential services. It also closed the Wheatville public school in 1932 while the federal government, insurance companies, and banks simultaneously redlined the neighborhood, labeling it as “hazardous” in order to have grounds for denying Black homeowners mortgage loans based on the location and implied condition of their properties.

Physical erasure of Wheatville continued over the ensuing decades. Black residents moved out and white people, many associated with The University of Texas, moved in. By the 1960s, student housing and fraternity or sorority houses stood where Wheatville homes, shops, and institutions once had. The house of one such white fraternity, Kappa Alpha Order—whose mission includes creating a lifetime experience “inspired by Robert E. Lee, our spiritual founder”—now sits in what was the center of the freed-person’s community.

Today, the area is almost exclusively non-Black; student and luxury apartments and condominiums are increasingly common. Zoning changes have been enacted to accommodate an increased number of students in new, large apartment and condo complexes. From 2004 to 2009, for example, 2,400 new units were constructed in the area. In 2012, owners renovated the building at 2402 San Gabriel St. and, in an attempt to recapture the building’s and community’s hidden Black history, opened Freedmen’s barbeque restaurant and bar in that space. In 2017, the City of Austin Historic Landmark Commission approved a proposal for Hilltop Development to construct a 134-unit, multi-family housing complex in a U-shaped configuration surrounding the building. One year later, Freedmen’s barbeque closed for business.

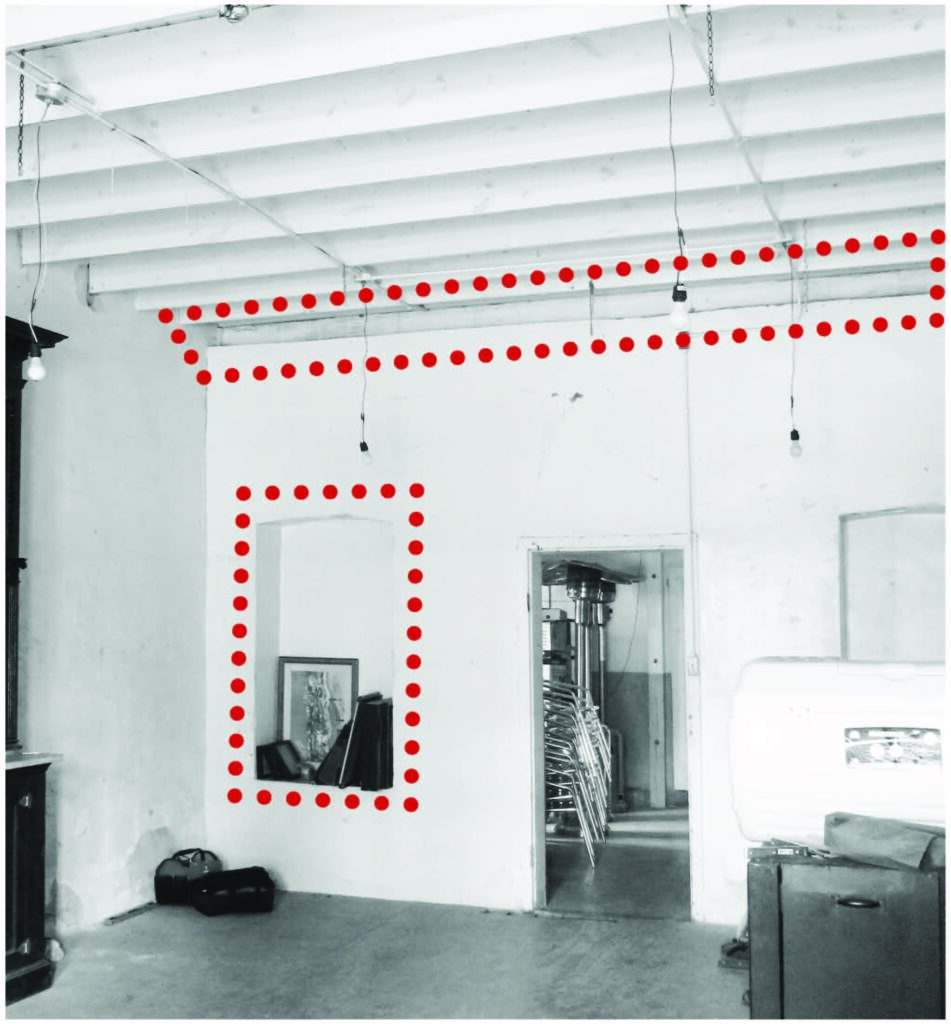

To mitigate yet another physical and historical erasure of the site’s Black history, in 2018 the Austin City Council voted to rename the two-story building at 2402 San Gabriel the “Jacob Fontaine Gold Dollar Building.” The current owners are now proposing a major change to the primary and only remaining visible feature representing the vibrant Black community that once existed in the area. They are requesting permission to remove the second story, Franzetti-era enclosed wood porch from the east façade, which is a wooden enclosure on the second floor, to create a balcony.

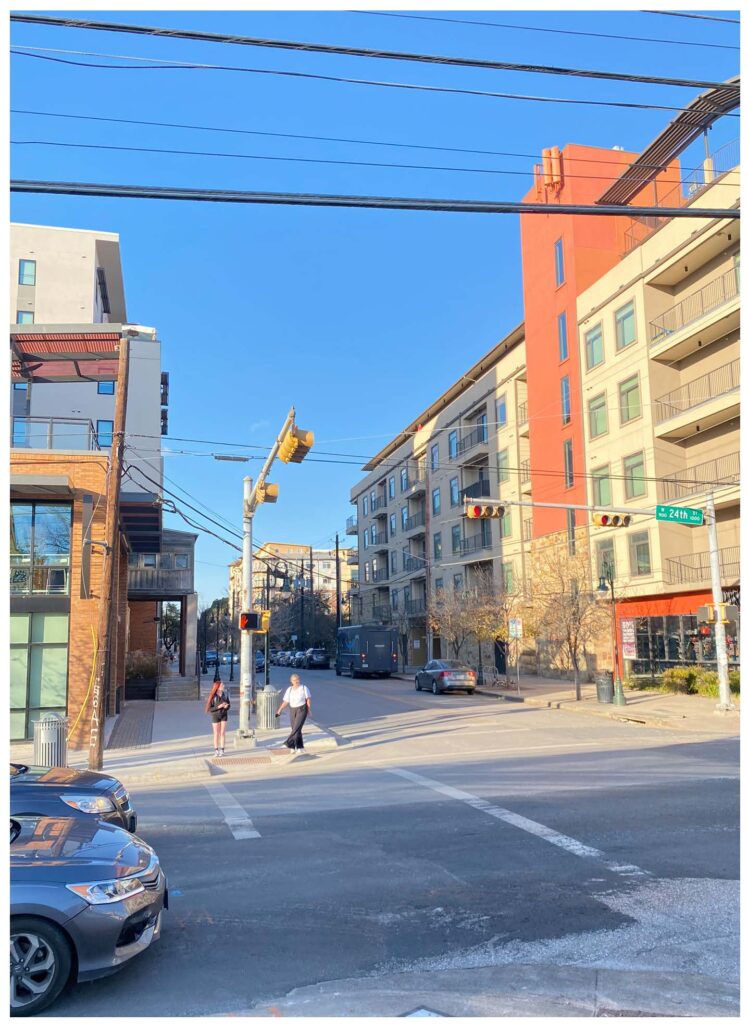

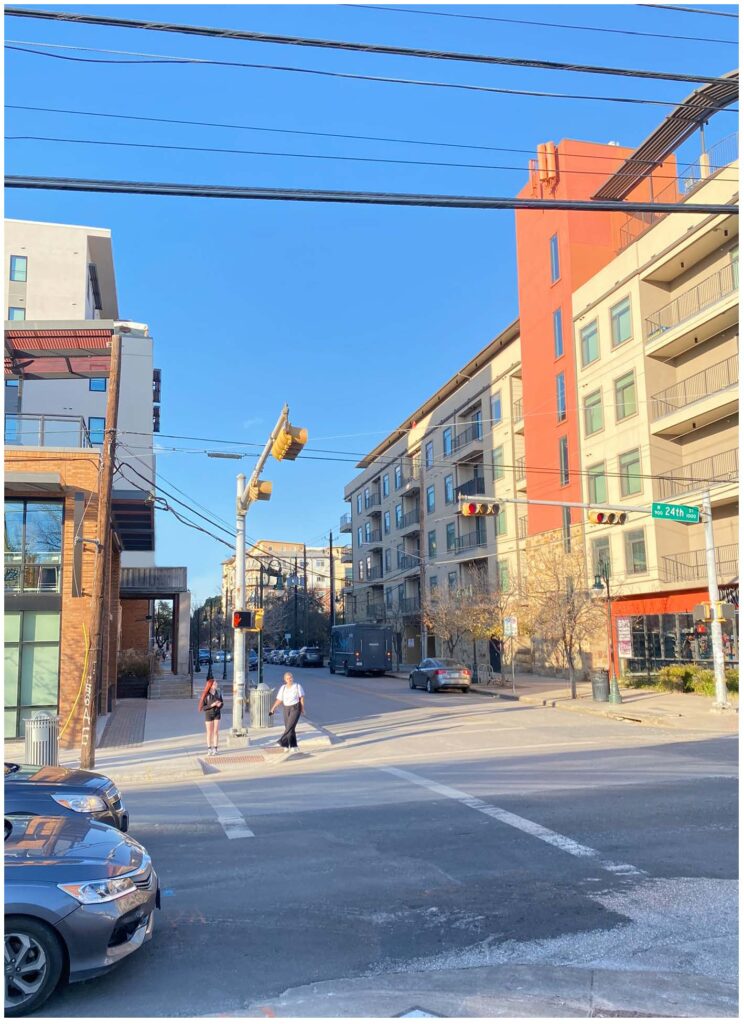

The Gold Dollar Building has come to represent the Black collective agency ingrained in what was the collective of freed Black people who lived in and alongside the structure at 2402 San Gabriel. It is now the single enduring artifact from the Wheatville community, with the enclosed porch the solitary aspect that is still discernable to the public, as the larger buildings dwarf the small structure (FIG 5). It is a character-defining feature of the building, clearly significant even to the untrained eye, and part of its historical narrative.

Granting the current request to remove the Gold Dollar Building’s porch without careful consideration of its structural evolution and historic context would undermine the unique visual feature of the structure that is the sole remaining visible symbol of Wheatville and would diminish the building’s standing in Black Austin’s collective history, further erasing Blackness in the city of Austin itself. Minimally, physical modifications should not be allowed to the building until experts can study the structure and make recommendations for preservation best practices.

Today, around 8% of Austin’s population is Black, a precipitous fall from the days of Wheatville’s prime. In many ways, the city’s growth and celebrated transformation is predicated upon the erasure of Blackness. In the aftermath of the systematic removal of the Black residents of Wheatville—including the then-owners of 2402 San Gabriel St.—the City of Austin and current owners of the property have a responsibility to preserve and commemorate that community’s lone remaining structure. This building should serve as a small but significant form of reparative recognition of Black presence, collectivity, and agency in our city. The Gold Dollar Building must be preserved and honored as a central symbol of the social memory of Blackness in Austin.

Tara Dudley

Charles Amos Horn

Edmund T. Gordon

Anna-Lisa Plant

February 2022

Bibliography

“Ancestry.Com – 1880 United States Federal Census.” Accessed January 15, 2020.

Ancestry.com. U.S., City Directories, 1822-1995 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.

“Apartments for Rent in Austin, TX | West Campus Apartments – Hilltop – Home.” Accessed January 15, 2020. https://www.hilltopatx.com/.

Austin City Directories in The Portal to Texas History. University of North Texas Libraries. https://texashistory.unt.edu/explore/collections/CIT/.

“Austin, TX Population – Census 2010 and 2000 Interactive Map, Demographics, Statistics, Quick Facts – CensusViewer.” Accessed January 15, 2020. http://censusviewer.com/city/TX/Austin.

Beauregard, Max, “2402 San Gabriel,” ARC 355 Project, University of Texas at Austin, 1973.

Burd, Gene A. “Fontaine, Jacob,” Handbook of Texas Online, accessed February 11, 2022, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/fontaine-jacob. Published by the Texas State Historical Association.

“Daily Democratic Statesman,” Daily Democratic Statesman, Austin, August 19, 1879: 4.

Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, A Pictorial History of Austin, Travis County, Texas’ Black Community, 1839-1920: The Black Heritage Exhibit (Austin, TX.: publisher not identified, 1970).

Diamante, Reena. “Historic Central Austin Building to Be Renamed After Freed Slave.” Accessed January 15, 2020. https://spectrumlocalnews.com/tx/austin/news/2018/11/20/historic-central-austin-building-to-be-renamed-after-freed-slave-.

Dudley, Tara, “Before West Campus: Rediscovery and Preservation of Wheatville’s African American Heritage,” Platform: Preservation in the Americas (2019-20): 8 – 11.

Fontaine III, Jacob, and Gene Burd, Jacob Fontaine: From Slavery to Greatness of the Pulpit, the Press, and Public Service (Austin, TX: Eakin Press, 1983).

Gibson, Campbell, and Kay Jung, “Population Division Working Paper – Historical Census Statistics On Population Totals By Race, 1790 to 1990, and By Hispanic Origin, 1970 to 1990 – U.S. Census Bureau,” 2005. https://www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps0076/twps0076.html#intro.

Gold Dollar, “Gold Dollar. The” Gold Dollar. The, 1876.

Gordon, Edmund, “The Gold Dollar Building and Black Erasure,” The End of Austin: an exploration of urban identity in the middle of Texas. Accessed February 11, 2022. https://endofaustin.com/2020/11/21/the-gold-dollar-building-and-black-erasure/

Grose, Charles William, “Black Newspapers in Texas, 1868–1970,” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Texas at Austin, 1972.

Pace, Katherine Leah, “Forgetting Waller Creek: An Environmental History of Race, Parks, and Planning in Downtown Austin, Texas,” Journal of Southern History 87(4), Nov. 2021: 603-644.

Hafertepe, Kenneth, “Abner Cook: Master Builder on the Texas Frontier,” Austin: Texas State Historical Association, 1992.

Hamilton, William Benjamin, Social Survey of Austin (Austin, TX: University of Texas, 1913).

Historical Landmark Commission, “Application for Certificate of Appropriateness Franzetti Store.” Accessed January 15, 2020. http://www.austintexas.gov/edims/document.cfm?id=284393.

Horn, Charles Amos, “The Franzetti Building at 2402 San Gabriel,” ARC 387G Project, University of Texas at Austin, 2011.

Kappa Alpha Order, “Wayback Machine,” September 28, 2007.

Lack, Paul D., “Urban Slavery in the Southwest,” PhD Thesis, Texas Tech University, 1973.

McDonald, Jason, Racial Dynamics in Early Twentieth-Century Austin, Texas (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2012). http://site.ebrary.com/id/10608689.

Mears, Michelle M., and Grace Will, Lead Me Home African American Freedmen Communities of Austin, Texas, 1865-1928 (Lubbock, TX: Texas Tech University Press, 2009).

“National Society of The Colonial Dames of America.” Accessed January 15, 2020. https://nscda.org/.

Tang, Eric, and Chunhui Ren, “Outlier: The Case of Austin’s Declining African-American Population.” Accessed January 15, 2020. http://www.ebony.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Austin20AA20pop20policy20brief_FINAL.pdf.

Thompson, Nolan, “WHEATVILLE, TX,” June 15, 2010. https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/hpw01.

Travis County Clerk Records in The Portal to Texas History. University of North Texas Libraries. https://texashistory.unt.edu/explore/collections/TRCPR/22.

Travis County (Tex.). Clerk’s Office. Travis County Clerk Records: Plat Record 1-2, book, 1877/1913; (https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth1407182/: accessed February 14, 2022), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, https://texashistory.unt.edu; crediting Travis County Clerk’s Office.

Tretter, Eliot M., “Austin Restricted: Progressivism, Zoning, Private Racial Covenants, and the Making of a Segregated City,” 2012. https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/handle/2152/21232.

“U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Austin City, Texas.” Accessed January 15, 2020. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/austincitytexas/LND110210.