Red River Community

The Red River community was a flood-prone community located in the riparian zones of the main branch of lower Waller Creek (below 19th (Magnolia/MLK) St.). As the enclave had no formal name, historian Michelle Mears named it after Red River Street, a flat transit and commercial corridor along which Black businesses clustered. A downtown residential and commercial enclave, it was concentrated between East 6th and 19th Street. Along with the Pleasant Hill and Robertson Hill communities, it formed part of a cluster of riparian freedom colonies located along lower Waller Creek.

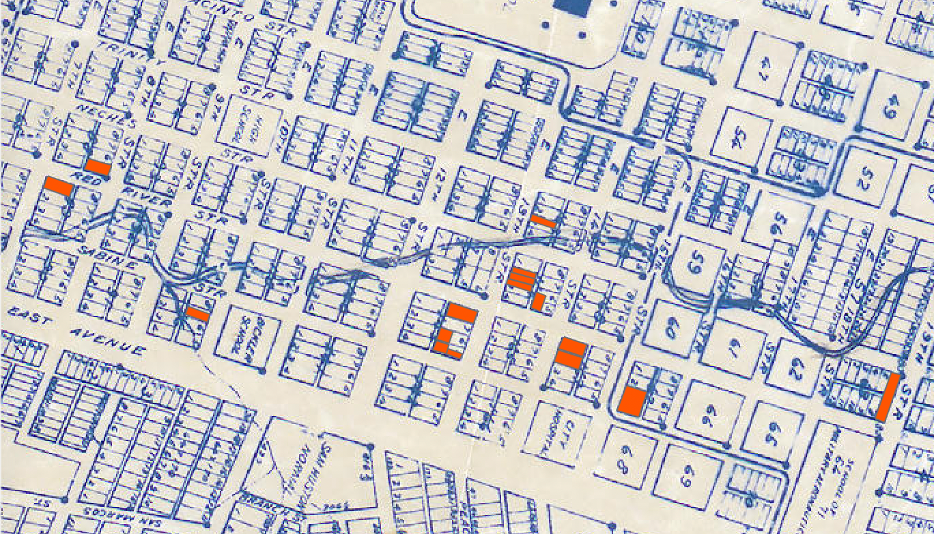

The community’s beginnings date to July 1869, when a record flood swept down the Colorado River, inundating the city as far north as 6th Street and causing the river’s tributaries– including Waller Creek – to back up and likewise flood. This event caused white landowners to begin selling undesirable and flood-prone parcels to Blacks, and the following month, a white man sold an undeveloped lot at Red River and East 11th Streets to a Black man, Edward Aldridge, who subsequently sold a division of his lot to another African American. Soon after, another white man sold a lot at Red River and East 12th Streets to Vince McCraven, a Black man from Mississippi, who likewise subdivided his land and sold to Black buyers. Waller Creek “meandered” through the properties.[1]

By the time work on Austin’s 1872 city directory began, the main branch of lower Waller Creek was home to an established Black residential and commercial community. One block west of Red River Street, there was the Colored Methodist Church, and along the creek’s downtown stretch there were dozens of Black residences and businesses, almost all located squarely within Waller Creek’s floodplains. Jeremiah Hamilton, a Black carpenter from Bastrop, Texas, and a member of the 12th Texas legislature, lived with his family at Red River and East 11th Streets, in a two-story triangular stone house they built. Out of the bottom story, they ran a grocery. Half a block down Red River Street there was another Black grocery and, next door, a Black shoemaker. One block east, on flood-prone Sabine Street, there was a Black poultry and vegetable peddler. The district was also home to four blacksmith workshops where nearly a dozen African American blacksmiths were employed. The enclave’s residents quickly founded the community-funded Evan’s Community School. In 1876, the school had 150 pupils. The Red River community was internally segregated by topography, with its poorest residents living in crowded shantytown communities along Waller Creek’s steep banks. For the next 100 years, the Red River community remained intact.

In addition to institutionalizing residential segregation and racist zoning policies, Austin’s 1928 city plan sought to use parks to socially landscape Austin’s lowlands, including the floodplains of lower Waller Creek. The plan’s authors, Koch and Fowler, recommended the city boost property values along the waterway by replacing its flood prone shantytowns with public parks, which would be integrated into the Waller Creek Parkway, or East Avenue Boulevard, a paved thoroughfare designed to serve the city’s automobilists. The planners wrote about the parkway,

The completion of this drive will entail the acquisition of certain cheap property along the banks of Waller Creek from Eighth Street to Nineteenth Street. Most of the property which will be needed is at present occupied by very unsightly and unsanitary shacks inhabited by negroes. With these buildings removed…remaining property will be of a substantial and more desirable type.[2]

Despite approving the Koch and Fowler plan, the city did not build the Waller Creek parkway, focusing instead on acquiring undeveloped lowlands in North and West Austin, where it built a parkway along Shoal Creek. The city straightened a bend in Waller Creek at 3rd Street, the site of white Palm Elementary School. Next to the school it built Palm Park, displacing shanties from the area.

Throughout the Jim Crow era, these were the only major developments along lower Waller Creek, and the Red River community, including most of its riparian shantytowns, remained in place. Black businesses – amongst them a funeral home, a print shop, at least two car garages, and multiple antique stores – remained clustered in the east end district’s flood- prone stretches. The first of these antique stores opened in 1918 at Red River and East 8th Streets and was run by Simon Sidle, a horse trader from Pflugerville, Texas. Sidle taught his daughter, Theresa, the tricks of the trade, and in the mid-1940s, she and her husband Tannie opened an antiques store at Red River and East 12th. They were soon joined by other secondhand dealers, Black and white.

By the mid 1960s, the east end was one of downtown Austin’s liveliest districts, home to inexpensive housing and hundreds of businesses. Red River Street had developed into a popular secondhand strip, lined with “we buy and sell anything” shops and fine antique dealers. According to Austin’s 1971 Black Business Registry, seven of these secondhand stores were Black run, amongst them Tannie and Theresa’s Antiques, which in the 1950s had moved to a larger building at Red River and East 11th Streets. The business registry also listed two black car mechanics on the same flood-prone stretch of East 7th Street as the Fowler Electric Company, a Black appliance repair shop. At the flood-prone intersection of Sabine and East 15th Streets, there was a Black drug store.[3]27 Meanwhile, Black (and brown) people continued living in shanty neighborhoods along Waller Creek’s banks.

In 1972, Austin’s urban renewal agency razed the east end’s northern half, dislodging Black people from their century-long hold on lower Waller Creek’s floodplains and, in the process, displacing nearly 150 businesses and over 200 families. Approved in 1968, the 144- acre Brackenridge Urban Renewal Project stretched from East 10th to 19th Streets and from Capitol Square east to Interstate Highway 35. According to project documents, it was designed to give the University of Texas, Capitol Square, and Brackenridge Hospital room to grow, and to enhance the area’s “environmental characteristics,” spurring new development. Brackenridge project documents made no mention of shacks along Waller Creek, speaking instead in general terms about overcrowded buildings and undesirable mixed uses. Urban renewal planners nonetheless did with Waterloo Park precisely what Koch and Fowler had recommended four decades before: to “enhance the economic value” of property along lower Waller Creek,[4] 28 they built a park – Waterloo Park – in Waller Creek’s floodplains, displacing Black and brown shanty neighborhoods from the area.

Contrary to planners’ expectations, the Brackenridge project did not stimulate new development, for in the mid 1970s, the city passed new floodplain ordinances that increased the cost of floodplain development, deterring would-be developers from the waterway. Its business strip disrupted, the once bustling east end languished; however, urban renewal did succeed in realizing Koch and Fowler’s vision for a segregated Austin. According to this vision, Austin’s Black district began and ended at East Avenue, which in the late 1950s was

converted into Interstate Highway 35. Black (and brown) settlement in lower Waller Creek’s floodplains frustrated these plans, turning Waller Creek – as opposed to East Avenue – into Austin’s color line. Along with the University East Urban Renewal Project, the Brackenridge project “removed [most of] the remaining Black families from along the west side of IH 35 and confined the East Austin community to the east side of this major traffic artery,”[5] shifting Austin’s color line from the creek to the highway, displacing Black residences and thriving Black businesses, and, to paraphrase Theresa’s niece, Dorothy McPhaul, killing a part of Austin’s history.[6]

References

Robena Estelle Jackson, “East Austin: A Socio-Historical View of a Segregated Community” (M.A. thesis, University of Texas at Austin, 1979), 119–20.

Michelle M. Mears, And Grace Will Lead Me Home: African American Freedmen Communities of Austin, Texas, 1865-1928 (Lubbock: Texas Tech University Press, 2009).

Katherine Pace, “Forgetting Waller Creek: An Environmental History of Race, Parks, and Planning in Downtown Austin, Texas,” Journal of Southern History 87.4 (2021), 603- 644.

—, “‘We may expect nothing but shacks to be erected here’: An Environmental History of Downtown Austin’s Waterloo Park,” Not Even Past (2022), https://notevenpast.org/we-may-expect-nothing-but-shacks-to-be-erected-here-an- environmental-history-of-downtown-austins-waterloo-park/

Koch & Fowler, A City Plan for Austin, Texas (Austin, 1928).

The Black Registry of Austin’s Businesses (Austin, 1971).

[1] Angela Parmelee, “Docent Training: Brief History of the Site of Symphony Square,” 1976, Folder 3, Box 2, Peggy Brown Papers, AR.2009.051, Austin History Center.

[2] Koch & Fowler, A City Plan, 22.

[3] The Black Registry of Austin’s Businesses (Austin, 1971), 7.

[4] Austin Urban Renewal Agency, Brackenridge Urban Renewal Project (Austin, 1967).

[5] Robena Estelle Jackson, “East Austin: A Socio-Historical View of a Segregated Community” (M.A. thesis, University of Texas at Austin, 1979), 119–20.

[6] Interview with Dorothy McPhaul by Amber Abbas, 2005, Lift Every Voice (African American Oral History Project), clip 3, in possession of Martha Norkunas, Middle Tennessee State University.