East Campus Community

The East Campus community was a Black neighborhood located just northeast of the University of Texas campus. Most of its residents lived on or between East 30th Street and what is now Dean Keaton Street (formerly 26th Street), and between what is now Medical Arts Street and Interstate Highway 35 (formerly East Avenue). A relatively small community, it did not have a name. As such, because of its location, we have named it accordingly.

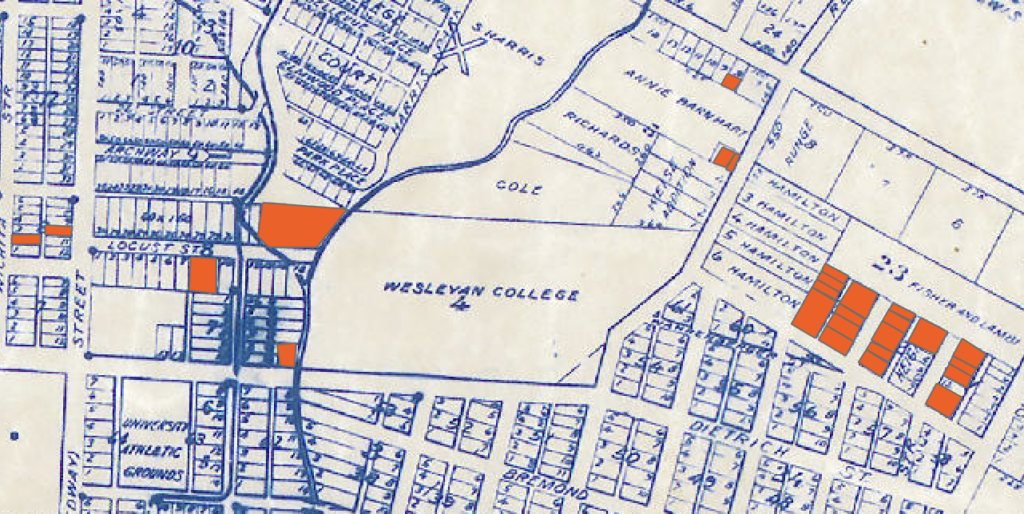

G. M. Brass, a “well known real estate dealer” who advertised and sold land around Austin and Travis County, first subdivided the area in 1904. In 1906, he began selling lots in the neighborhood to Black people. Historic maps show a tributary of Waller Creek running through the subdivision, providing a logical explanation for why Brass sold properties in the area to African Americans: quite simply, the land was likely flood prone.

Data from the 1910 census shows eight Black households in what was then a sparsely settled area. By 1920, the neighborhood was home to close to two dozen Black households, including 18 Black homeowners. Most residents worked as laborers, yard workers, cooks, domestic workers, porters, and in other working-class occupations, but Black residents also included a teacher, a minister, and a dentist. According to census data, in 1940, the East Camps community remained home to a significant Black residential cluster, home to a good two dozen Black households. Unlike other black settlements in Austin, it was an exclusively residential neighborhood, without a school, church, or businesses.

As Austin’s Mexican population increased, Hispanic people also settled in the neighborhood. In the late 1950s, the city began approving zoning changes in the area, allowing developers to build apartments for the University of Texas’ growing student population.

While the East Campus community was not directly affected by implementation of the 1928 master plan, the successive location of major traffic arteries in the area negatively impacted the neighborhood. The first of these traffic arteries was Interstate Highway 35, which replaced East Avenue in the late 1950s. Initially, the Texas Highway Department and Austin officials decided to run the highway through West Austin, for an East Avenue route encountered “a high bluff” south of the river, increasing highway construction costs. Aware that white residents would object to these plans, the highway department promised to cover the cost of bridging the Colorado River. As there was no bridge west of downtown, the city accepted the deal, but when officials made their plans public in 1940, West Austin’s affluent, white residents protested. They took their complaints to highway department meetings, and planners returned to the drawing board. In 1947, when city officials hosted another round of public meetings, they informed residents that Austin’s new “super highway” would run along East Avenue, cutting through East Austin’s working-class, mixed-race, and largely Black communities, who had limited political clout with which to contest city planning decisions.[1]

Hundreds of feet wider than East Avenue, I-35 displaced homes, businesses, churches, and a college, triggered a flurry of zoning changes from residential to commercial, and increased noise and air pollution along its route, making nearby communities less pleasant and less safe places to live. Less than a decade after the highway’s completion, the city decided to turn 26th Street – then a discontinuous, small neighborhood road – into a major thoroughfare that would connect I-35 to Guadalupe Street and, eventually, to Lamar Street and Mopac. Completed in the early 1970s, the new street (today’s Dean Keeton) was designed to reduce traffic congestion and give UT “a major entrance road” from the highway.[2] University of Texas regents assisted with the project, voting to acquire a portion of the property needed for the road’s right-of-way. As with I-35, 26th Street’s construction displaced homes and businesses from along its route, including land in the East Campus community needed for connecting ramps between the freeway and the new street. Once completed, the thoroughfare brought more traffic and noise and air pollution to the East Campus neighborhood.

In 1973, the city voted to route a third major thoroughfare, Red River Street, through the middle of the neighborhood. The previous year, UT regents announced that they did not intend to renew the city’s lease of the Municipal Golf Course, located on UT-owned land in West Austin. In response, the city made a deal with the regents. In exchange for an additional 14-year lease, the city would relocate and widen portions of Red River Street, turning the road into a key thoroughfare and allowing UT to close San Jacinto Street, which runs through the university campus, to public traffic. This relocation involved routing Red River Street along an “s-curve” that cut through the East Campus community.

Residents protested the city’s plans, arguing at public hearings and in petitions that a modified Red River Street would result in the destruction of numerous large live oak trees, three large apartment complexes, and numerous houses, and would increase visual, noise, and air pollution in affected neighborhoods. Despite these objections, the city relocated Red River Street, gutting a central swath of the East Campus neighborhood. Notably, however, it “bowed to pressure” from white, middle-class residents who lived in a neighborhood just north of East Campus; it opted not to widen Red River Street between 32nd and 381/2 streets, as it had initially planned.[3]

While more research is required to determine just when and how quickly Black homeownership in the East Campus neighborhood declined, by 1986, the community had disappeared. That year, in an interview with historian Michelle Mears, an elderly Black resident of Austin, Toby Scott, described the area “where Villa Capri Hotel is now [along I35, between 23rd and 24th Streets] and just a little north.” He recalled, “There was a group of blacks that lived in that area.” By implication, when the interview was conducted, this group was no longer there.

[1] Morris Midkiff, “Special Council Session Receiving Further Protests Against Shoal Creek Route,” Austin Statesman, January 5, 1940, pp. 1, 15; “Interregional Routes Approved,” Austin American, August 8, 1947, 4.

[2] D. Evans, “Regents to Assist Roadway Linkup,” Austin Statesman, February 1, 1969, 1.

[3] B. Hight, “Council scraps street-widening contract: Neighborhood pressure prevails in controversy over Red River,” Austin American Statesman, March 3, 1978, B5.