Wheatville

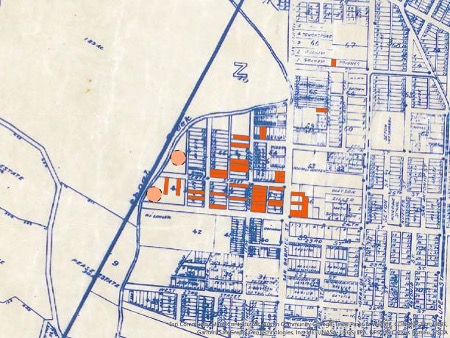

Wheatville was a Black freedom community located in the northwestern portion of what is now the West Campus neighborhood, just west of the University of Texas (UT) campus. The 1910 U.S. census reported 73 Black households and 558 Black individuals residing in a community bordered on the south and north by West 24th and 28th Streets, respectively, and on the west and east by Shoal Creek and Rio Grande Street. Though the community’s area and population declined after 1910, the 1940 census recorded 42 Black families and 146 Black residents in the community. By the late 1970s, no Black homeowners remained in the area.

It is possible that the community’s history begins before the Civil War. In many southern antebellum cities, upwards of 30 percent of enslaved residents “lived out” of their owners’ homes.[1] Many squatted in clusters on the far outskirts of town. Perhaps some enslaved people lived in what would become the Wheatville area – then located in Austin’s far northern outskirts – forming a residential cluster and, after emancipation, attracting more Black people to the vicinity.[2]

In any case, by 1867, the Wheatville community was taking shape. That year, four Black Baptist ministers, including prominent Reverend Jacob Fontaine, met under a giant oak tree at West 25th and Leon Streets. There, the ministers agreed to divide Texas into four divisions, each of which would become home to a Baptist association whose reverends travelled “by horseback, horse drawn wagons, mules, and oxen” to minister to Black communities throughout the region.[3]

That same year, James Wheat, a formerly enslaved farmer, moved from Arkansas to the Wheatville area with his wife and their six children. In 1868, the first documented Black landowner in the area Joseph Caruthers, a freedman from North or South Carolina, acquired property at 900 West 24th Street, from John M. Thomas. The following year, Wheat bought three parcels from Thomas, including present-day 2409 San Gabriel Street. Other African Americans bought or rented land nearby. At the time of Wheatville’s founding, the entire area was already the property of White landowners. Those Blacks who owned property were only able to do so through purchase, a considerable feat for the formerly enslaved.

By 1876, Wheatville residents had organized a community-managed and funded elementary school, attended by 66 students that year.[4] According to census data, by 1880, the community was home to 26 households and 125 persons. [5] The following year, the city opened a Black elementary school, Wheatville school, located at West 25th and Leon Streets. [6]

Wheatville residents worked in various sectors of Austin’s racialized workforce – they were craftsmen, farmers, ministers, nurses, teachers, teamsters, laundresses, cooks, domestics, merchants, and more. Many planted crops and tended gardens and livestock on their properties, and most likely, they hunted and gathered timber in Shoal Creek’s forested valley.

Early residents included George Franklin, a formerly enslaved carpenter who purchased land at 2402 San Gabriel in 1869 and constructed a stone building. Today, this building forms the original core of the only contemporary physical remnant of Wheatville.[7] Now known as the Jacob Fontaine Gold Dollar Building, the structure housed Rev. Jacob Fontaine and his family, who settled in Wheatville in the late 1860s. The family purchased property next door at 2400 San Gabriel Street. From there, Fontaine printed Austin’s first Black newspaper, The Gold Dollar. An important part of the fabric of the semi-autonomous Wheatville community, the newspaper was also an instrument in the struggle for racial economic, political, and social justice in the Reconstruction Era.[8]

A prominent Black Republican pastor, editor, teacher, and businessman, Fontaine was a target of racial violence. In 1879, unknown assailants burned his home and printing press to the ground as Austin’s fire companies watched. After the fire, the Fontaine family periodically rented the Gold Dollar Building as a residence and business. In 1887, Fontaine founded the New Hope Baptist Church. It is possible that he held church services in the Gold Dollar Building. The Fontaine family home at 2400 San Gabriel Street and the stone building next door – the original locations of both the Gold Dollar newspaper and of New Hope Baptist Church – make the northwest corner of 24th and San Gabriel one of the most significant locations in Black Austin history.[9]

The University of Texas flagship campus opened just east of Wheatville in 1883. As Austin grew, elite and middle-class residents associated with the University created new neighborhoods in North Austin. In 1890, land developers built Austin’s first electric streetcar line, connecting the company’s new North Austin suburb, Hyde Park – located just north of UT – to the city center. To boost Hyde Park property values, developers marketed the suburb as White-only, “free from nuisances and an objectionable class of people.”[10] Soon after, another streetcar line was laid along Rio Grande Street, Wheatville’s eastern border. This had an immediate impact, pushing White housing to this edge of the community.

By and large, however, White people did not settle too far west of Rio Grande Street or north of 24th Street, and the Black community continued growing. An indication of this growth is the steady increase in the Wheatville elementary school population, which went from 60 students in 1896 to 97 in 1904. Also in 1904, Wheatville became home to a second church, the Pilgrim’s Home Baptist Church. By 1915, Wheatville school enrollment had increased to 141.[11]

By this point, however, the Model T Ford, the first affordable automobile, had hit the market. Sales were booming, and as the decade advanced, increasing numbers of White people settled near the Wheatville area. These changing demographics are reflected in the city’s decisions regarding garbage disposal. Sometime around 1912, the city began using the Shoal Creek ravine at the end of West 25th and 26th Streets, “almost in the very center of Wheatville,” as a dumping ground for waste of all kinds, including garbage and human and animal excrement. That year, Austin’s Special Health Inspector, William Hamilton, conducted a survey of sanitation hazards around the city. He wrote about the dump, “The drivers are not always careful to dump the trash in that one place. Frequently the wagons are emptied into a street or alley before the dump is reached,” turning Wheatville’s unpaved streets and alleys into stinking cesspools and noxious disease vectors.[12]

In early 1918, demonstrating concern for growing number of White residents in West Campus, the city relocated the Wheatville garbage dump. A local newspaper explained, “within the past year” the dump has occasioned “vigorous protests from all the northwest part of town, particularly from those who reside in the immediate vicinity. They have complained of smoldering fires and smoke, bad odors, and the insanitary condition generally.”[13] In response, the city “began dumping on a negro’s property half a mile to the southwest.”[14]

Shortly thereafter, Wheatville household numbers began to drop from over 70 households in 1920 to under 50 ten years later. This drop resulted from several related factors, most prominently a concerted attack by the city on Black homeowners associated with city planning policies adopted in 1928. That year’s City Plan directed that all municipal services for Black people be concentrated in East Austin. Already, Austin’s only Black high school was located to the east. In the 1930s, the city also built its only Black library and park in East Austin. The city also paved roads and installed sewers in East Austin, while refusing such services to Black communities to the west. And in 1932, it closed the Wheatville school

Around the country, the automobile – along with trucks and tractors, which lowered construction costs – turned formerly far-away land into prime real estate, triggering the rapid development of automobile suburbs. Like streetcar suburbs, automobile suburbs were White only by design. The 1928 Plan was designed to facilitate this kind of development, and indeed, its authors imaged that as the city pushed and pulled its Black residents into East Austin, Wheatville would develop into a White suburban neighborhood of single-family units.

A prime example is Pemberton Heights, a “restricted” (White) suburb that opened in 1927 directly across Shoal Creek from Wheatville. In contrast to the Black community, it had gas, water, and sewers. The June 12, 1927, issue of Austin Statesman held, “it is mere coincidence” that Pemberton Heights was platted by “the engineers now engaged in the construction of Austin’s City Plan.” It seems no coincidence, however, that the City Plan called for a paved extension of 24th St skirting Wheatville and across Shoal Creek, the building of an auto bridge across the creek, and the construction of a motor way along the creek. By 1928, a concrete bridge over Shoal Creek, had been built, which was expanded by the city in 1938. The next year the city began construction of Lamar Boulevard, which passed right through the Wheatville community.[15]

The policy to replace Wheatville Blacks with middle class whites was only partially successful. By 1940, the loss of the Wheatville school in 1932 and then New Hope Baptist Church, which relocated to East Austin in [], and a 42% reduction in the number of households from 1920 indicate that the community and its civil society was fading. However, the community continued to exist, and the continued presence of Blackness staved off the conversion of the space to White middle-class suburbia, which by the late 1930’s had begun to surround the community on all sides.

The final denouement of the Wheatville community was the city’s approval in 1946 of the zoning necessary to create what amounted to a fraternity row along Pearl Street, just east of Wheatville’s remaining core.[16] The zoning change in this area from A single family dwellings to B residential, which permitted fraternity houses, was consistent with the core racial policy element of the 1928 Plan – create a “negro district” and “draw the negro population to this area.”[17] It is important to note that the zoning changes made for fraternities and sororities opened the door to the construction of apartment buildings for students as well. The UT student population exploded immediately following WWII, but there was no increase in university housing, resulting in a crisis for the university. In response, UT constructed temporary wooden frame buildings for classrooms. As a last-ditch effort to address the issue of scarce student housing, the UT administration encouraged, supported, and enabled the expansion of fraternities and other forms of collective student housing. By virtue of its proximity to UT, the sparsity of previous development, and the relatively low cost of land – the latter two due to the association of the space with blackness – fraternities-sororities, real estate speculators, the university, and the city developed Wheatville and its immediate vicinity into a fraternity-sorority and generally student dominated neighborhood.

For example, in 1947 Delta Kappa Epsilon, represented by two lawyers and six former fraternity members who included a general and a lieutenant colonel, showed up at a Board of Adjustment meeting and presented a petition signed by the infamous Theophilus S. Painter, President of the University of Texas; James C. Dolley, Vice-President; Arno Nowotny, Dean of Student Life; Jack Holland, Assistant Dean of Men; and others. They were requesting a zoning change, which they received, so that the fraternity could build a $100,000.00 house on its property at Pearl and West 25th Street, which had been left out of the 1946 zoning change in the area.

By 1955, the social character of Wheatville and its vicinity had been transformed. In its February 20, 1955, issue, the Austin American Statesman gushed:

“The new multi-million-dollar fraternity row west of the University of Texas campus is still growing. … The building of several such mansions since World War II already has done much to turn the area between the University and Lamar Boulevard into a sort of “Hollywood strip.” Now comes the news that several other fraternities and sororities have approved building plans having a magnitude similar to those already completed.

The Greek organizations’ move into Wheatville did not stop in the 50’s. Today, within the limits and on the near periphery of what was Wheatville in 1910, there are now 20 fraternities and sororities.

In 1940, the forty-two Black households still residing in the core of historic Wheatville constituted an historically and culturally cohesive community of families. By 1977, the estate of the last Black property owner had been sold and would be replaced by fraternities and other student housing. In the end, UT’s corporate logic of expansion facilitated by the Greek sons and daughters of Texas elites accomplished what the 1928 plan’s denial of services policy began but only partially achieved.

[1] Richard C. Wade, Slavery in the Cities: The South, 1820-1860, New York: Oxford University Press, 1964.

[2] Richard C. Wade, Slavery in the Cities: The South, 1820-1860, New York: Oxford University Press, 1964.

[3] “History of St. John,” https://www.stjohnbaptistassociation.org/history-of-st-john/.

[4] Nola Thompson, “Wheatville, TX (Travis County),” Texas State Historical Association, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/wheatville-tx-travis-county.

[5] https://ctxretold.org/black-communities/wheatville/

[6] The second school was located in the Robertson Hill community, just east of downtown.

[7] “Preserve the Jacob Fontaine Gold Dollar Building,” Retelling Central Texas History, https://ctxretold.org/preserve-the-jacob-fontaine-gold-dollar-building/.

[8] Edmund T. Gordon, “The Gold Dollar Building and Black Erasure,” The End of Austin (2020), https://endofaustin.com/2020/11/21/the-gold-dollar-building-and-black-erasure/.

[9] “Preserve the Jacob Fontaine Gold Dollar Building,” Retelling Central Texas History, https://ctxretold.org/preserve-the-jacob-fontaine-gold-dollar-building/.

[10] Austin Board of Trade, 1894, 36, quoted in Eliot Tretter, “Austin Restricted: Progressivism, Zoning, Private Racial Covenants, and the Making of a Segregated City,” Final Report Prepared and Submitted by Eliot M. Tretter to the Institute for Urban Policy Research and Analysis (2012), 2.

[11] N. Thompson, “Wheatville, TX (Travis County),” Handbook of Texas online, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/wheatville-tx-travis-county, “Austin Schools,” The Statesman, September 4, 1915, 4.

[12] William B. Hamilton, A Social Survey of Austin (Austin, 1913), 53-54.

[13] “New Dumping Place for City’s Trash,” The Statesman, February 1, 1918, 6.

[14] “Will Use Trash to Fill Gulch,” The Statesman, February 1, 1918, 4.

[15] Koch & Fowler, A City Plan; “Pemberton Heights Newest Residential Addition Is Opened: J. B. Riley Is Named Sales Agent; Model Home Under Construction.” The Austin American, June 12, 1927.

[16] Austin City Council, “Minutes of the City Council of AUSTIN, TEXAS Regular Meeting February 6,1947,” 1947, https://www.austintexas.gov/edims/document.cfm?id=88630.

[17] Koch & Fowler, A City Plan.

References

Tara Dudley, “Before West Campus: Rediscovery and Preservation of Wheatville’s African American Heritage,” Platform (2019-2020), https://issuu.com/utsoa/docs/2019- 20_utsoa-platform_v4_1028.

Tara Dudley, Charles Amos Horn, Edmund T Gordon, and Anna-Lisa Plant. “Preserve the Jacob Fontaine Gold Dollar Building – RETELLING CENTRAL TEXAS HISTORY,” 2022. https://ctxretold.org/preserve-the-jacob-fontaine-gold-dollar- building/.

Edmund T. Gordon, “The Gold Dollar Building and Black Erasure,” The End of Austin (2020), https://endofaustin.com/2020/11/21/the-gold-dollar-building-and-black- erasure/.

Koch and Fowler. A City Plan for Austin, Texas. City of Austin, 1928.

Michelle M. Mears, And Grace Will Lead Me Home: African American Freedmen Communities of Austin, Texas, 1865-1928 (Lubbock: Texas Tech University Press, 2009

Thomas, Daniel Josiah. “The Enslaved and the Blind: State Officials and Enslaved People in Austin, Texas.” Not Even Past, December 4, 2019. https://notevenpast.org/the- enslaved-and-the-blind-state-officials-and-enslaved-people-in-austin-texas/.

Nola Thompson, “Wheatville, TX (Travis County),” Texas State Historical Association, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/wheatville-tx-travis-county.

Eliot Tretter, “Austin Restricted: Progressivism, Zoning, Private Racial Covenants, and the Making of a Segregated City,” Final Report Prepared and Submitted by Eliot M. Tretter to the Institute for Urban Policy Research and Analysis (2012).